It’s safe to say that the vertical farming craze has officially taken off. With land space and water availability becoming more of a factor in the agricultural equation, farmers worldwide are jumping at the chance to build up rather than out. While we credit the contributions corporate innovators like Bowery have made to the progress of the field, hydroponics as a farming technique is far from a new phenomenon.

Ancient Roots

You wouldn’t necessarily think it, but vertical farming has its origins in the earliest ages of recorded history. Uncovered Greek writings point to the starting point as 600 BC. Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II set out to build an irrigation system that would allow for planting crops typical of the more northern Media, a part of now-Iran that was also the birthplace of his wife, Amytis.

The result was the famous Hanging Gardens, commonly thought to be one of the seven wonders of the ancient world — or eight, depending on who you ask.

The 75-foot high setup is said to have featured flowing waterfalls that cascaded down a beautiful tower that enshrined multiple levels of crops, all made possible in the desert environment some 60 miles south of modern Baghdad, Iraq.

The true location of the Hanging Gardens has since been disputed. Modern historians like Oxford’s Dr. Stephanie Dalley point to ancient texts that describe the wonder as the construction of Assyrian king Sennacherib some 100 years prior, a claim backed by evidence of a complex irrigation system uncovered by modern excavations of the Assyrian capital of Nineveh.

Additional texts indicate that the Greek scholars were confused by the fact that Sennacherib deemed Nineveh the “new Babylon” following the Assyrians’ conquering of the Babylonian empire in 689 B.C.

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic records dating back to several hundred years B.C. also describe growing plants in water along the Nile without soil. Floating gardens and rice production were similarly documented in China by Marco Polo during his travels in the 13th century.

Aztec Innovation

Nearly 2,000 years later, the Aztecs were on the precipice of a similarly impressive agricultural innovation. The civilization made its way to what is now Mexico Valley back in the early 14th century, quickly founding the capital city of Tenochtitlan on the shore of Lake Texcoco. The people were soon made aware of an unexpected lack of available land.

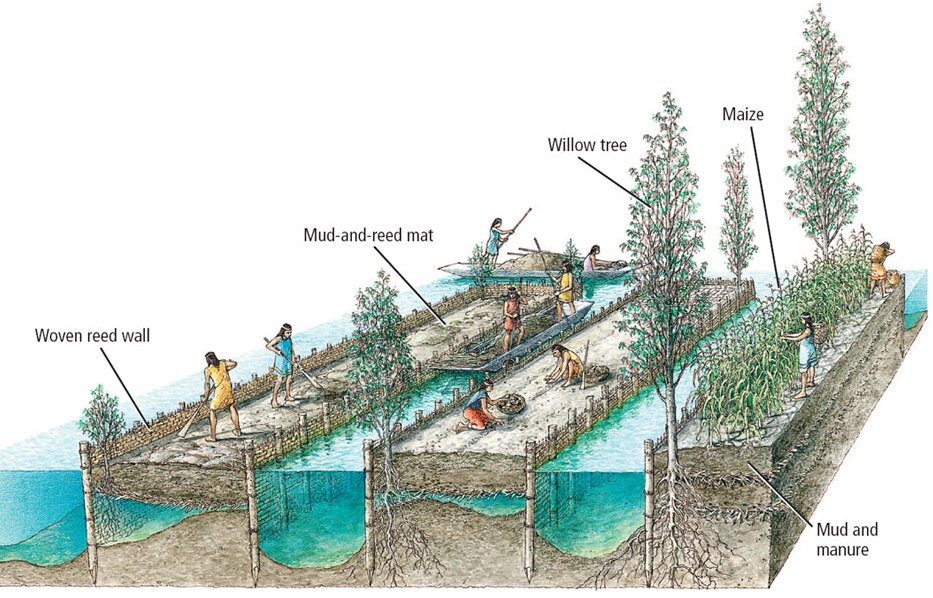

Faced with famine or another mass migration, the Aztecs developed a solution by creating chinampas, large raft-like structures made from reeds that supported soil beds atop the water’s surface.

These floating gardens sustained the Aztec population for centuries until colonization by Spanish settlers.

“Chinampas are not just a productive and sustainable agro-ecosystem technique, but they are also representative of the Aztec culture and carry the legacy of Indigenous people who taught us how to relate to nature, be part of it and live with it,” Patricia Perez-Belmont, founder of Umbela Sustainable Transformations told the BBC.

The 17 Century And Beyond

The centuries that followed saw an intermittent interest in vertical farming from modern societies, especially since the availability of farmable land wasn’t as much of a question as it is today. However, there were still a few key innovations.

Starting in 1600, Jan van Helmont proved that a willow shoot given consistent water over a long period (five years in this case) would grow to full size, with minimal changes to the weight of the soil. This discovery meant that it was mainly water, not soil content, that determined whether a plant could reach full size.

It wasn’t until the 1860s that Germany’s Julius von Sachs coined the term “nutriculture” in reference to his studies, which indicated an ideal nutrient mix that determined the eventual nutrient content of the plant.

Building on van Helmont’s findings and von Sachs’ discoveries, William Federick Gericke coined “hydroponics” in the 1930s. It’s derived from two Greek words, “hydro,” meaning water, and “ponos,” meaning labor — “water-working.”

While working at the University of California, Berkeley, he grew 25-foot-tall tomato vines using water and nutrients. The results prompted further studies on nutrition in practical, commercial crops.

Today, after advances by the U.S. military in the 1940s and 1950s and further study, hydroponics takes past concepts and applies them through a digitized lens. Monitoring and automation technology are crucial, increasing efficiency. Given the need for sustainable farming, the practice will undoubtedly keep expanding, adding to its long legacy.